![]() On occasion, one experiences a confluence of comments on the same subject that amounts to a sign, a call to action. And so it was last week when Shannon and Marcia both mentioned cheese. Shannon turned my attention to a list of legendary parties that included President Andrew Jackson’s Cheese Party at the White House. And Marcia wrote about Sausage Cheese Balls on Facebook. Clearly, I was meant to write something about cheese.

On occasion, one experiences a confluence of comments on the same subject that amounts to a sign, a call to action. And so it was last week when Shannon and Marcia both mentioned cheese. Shannon turned my attention to a list of legendary parties that included President Andrew Jackson’s Cheese Party at the White House. And Marcia wrote about Sausage Cheese Balls on Facebook. Clearly, I was meant to write something about cheese.

To begin, I read about the the cheese that made its way to Andrew Jackson in History of Oswego County, New York, 1789-1877 and in a few modern accounts as well. But I smelled something other than cheddar. The dates were all over the place, the duration of the cheese’s stay in the White House varied, the scholarship was careless.

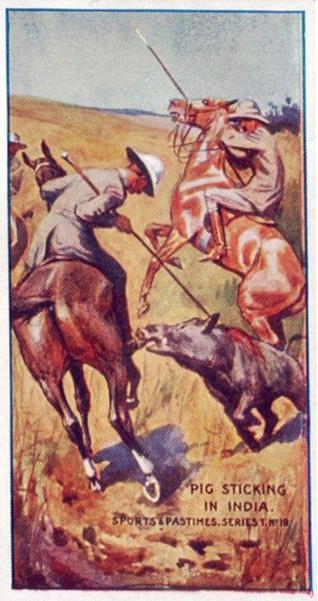

And so before the big payoff (Marcia’s recipe), I must set the record straight on the Cheese Party, also known as the Grand Cheese Levee of 1837:

During the presidency of Andrew Jackson, in 1835, a dairy farmer near Sandy Creek, N.Y., decided to make a giant wheel of cheese and give it to the president. The farmer was Colonel Thomas S. Meacham and his 1,000-acre farm was on the old Salt Road (today’s Route 11) in a small community about 40 miles north of Syracuse. Col. Meacham earned his title from his service in the War of 1812, and gathered his milk from a formidable herd of 154 cows who were fed on grass, hay and a half bushel of carrots each, daily.

Meacham built a gigantic cheese press with 24 staves, one for each state of the Union, and a hickory hoop, in honor of “Old Hickory.” Into the press went the curds from five day’s worth of milk and out of it came a wheel of cheese two feet in depth, four feet in diameter, eleven feet in circumference, weighing 1,400 pounds. He also made smaller cheeses, about 700 pounds each, to be given to the cities of Rochester, Utica, Troy, Albany and New York, and to Governor Marcy of New York, Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, Vice President Martin Van Buren and the U.S. Congress. The gifts were to serve the dual purpose of thanking the dignitaries for their service and publicizing the cheese-making prowess of Oswego County dairymen.

(The Rochester cheese was delivered earlier, on October 14th, and auctioned off on January 1, 1836, raising more than $1,000 for that city’s Fireman’s Benevolent Association.)

In November, the cheeses were loaded onto a wagon decked with flags, and began their journey from Sandy Creek, drawn by 24 teams of gray horses (48 horses in all). It was an impressive train and attracted hundreds of followers. Col. Meacham stopped the mile-long procession in Pulaski to display the cheeses, and then headed west to Port Ontario.

On November 15, 1835, to the accompaniment of cheers and cannon salutes, the boat, cheeses and Col. Meacham set sail for Oswego, some 20 miles distant. After a brief display in Oswego, the cargo was shifted to a canal boat to travel south to Syracuse, and then sent east. On November 17th and 18th, the cheeses were displayed in Utica and Troy before traveling to Albany for another showing. From the state capital, the cheeses made their way down the Hudson River to New York City.

In New York, Meacham put his cheeses on display at the Masonic Hall, and one of the 700-pound wheels was sold to the St. Nicolas Society for its annual banquet at the City Hotel. The quality of the cheese was said to be excellent.

On December 4th, the cheeses were joined by a 400-pound roll of butter sent from Sandy Creek by Mrs. Meacham. Displayed vertically, the roll reminded one New York Spectator reporter of “Cairo and the Pyramids—Pompey’s Pillar and Cleopatra’s Needle.” After their star turn at the Masonic Hall, the remaining cheeses were conveyed to the store of S. & W. Hotailing near Coenties Slip, a shipping inlet on the East River in lower Manhattan.

On December 8th, Meacham offered one of the cheeses to Sen. Daniel Webster, who was passing through New York on his way to Washington D.C. Sen. Webster visited Hotailings’ and selected a 750-pound wheel. He had it sent to Boston where, in January of 1836, “Meacham’s Brobdignagian cheese” was exhibited at Faneuil Hall. A few days after Webster’s visit, the 1400-pound cheese and the remaining 700-pound cheeses were loaded onto a boat and taken down the Atlantic coast to the Delaware River and thence to Philadelphia for another viewing. On December 31st, the cheeses arrived in Baltimore via Chesapeake Bay, and the next day made their way to Washington via the Potomac River.

On New Year’s Day, 1836, President Jackson accepted the mammoth cheese from Thomas Meacham and reciprocated with twelve bottles of wine from the White House cellars. (One account notes that Meacham also gave a painting to the President, but does not specify the artist or subject.)

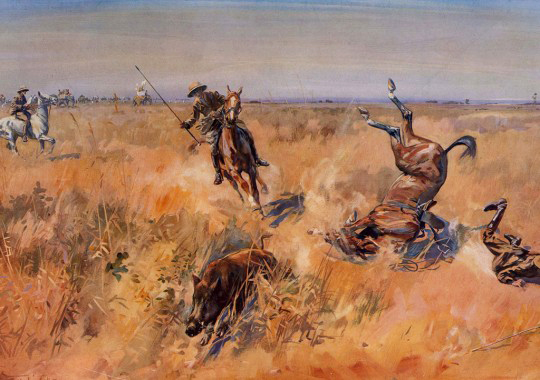

![]()

For all of 1836 and an early part of 1837, the 1400-pound wheel of cheese sat in the entrance hall, the Vestibule, of the White House. (Some later accounts say the cheese was moved to the East Room, but this differs from accounts published at the time.) It is said that the giant cheese ripened much as a giant cheese could be expected to do in the days, weeks and months that passed.

Then, in a letter of February 4, 1837, Jackson wrote, “I intend to have eaten on the 22nd instant, my large cheese, presented by my friends of the state of N. York – can you, and my friend Seeper be here & partake of the feast – see him if you please, present him my kind regards, & ask him for me to partake with me on that day of this feast, & any of your friends who may wish to accompany you – it will be my last & only public day.”

And so, on February 22, 1837, George Washington’s birthday, the President opened the doors of the White House for his final levee (public reception) and invited the people of the capital city to polish off the giant wheel of cheese.

A reporter who went by “O.P.Q.” and served as the Washington correspondent of the New York Express, described the scene:

“The old Romans talked of democracy, and the Greeks pretended something in that way. But for the genuine, pure, patent-right democracy, it’s our government against the world! This is Washington’s Birth day, you know. The President, the departments, the Senate, and we who are mightier than all—we the people, I mean—have celebrated it by eating a big cheese! The President’s house was thrown open. The multitude swarmed in. The Senate of the United States adjourned. The representatives of the various departments turned out. Representatives in squadrons left the capitol—and all for the purpose of eating cheese!

“Mind you, I don’t laugh at it. Who has a better right to eat cheese than we? It is all the spoils we can get, and as others nibble at the Treasury, here on earth should not we the people nibble at a big cheese?

“Mr. [Vice President Martin] Van Buren was there to eat cheese. Mr. [Daniel] Webster was there to eat cheese. Mr. [Levi] Woodbury [Secretary of the Treasury], Colonel [Thomas Hart] Benton, Mr. [Mahlon] Dickerson [Secretary of the Navy], and the gallant Colonel J. Trowbridge were eating cheese. The court, the fashion, the beauty of Washington, were all eating cheese. Officers in Washington, foreign representatives in stars and garters; gay, joyous, dashing, and gorgeous women, in all the pride and panoply and pomp of wealth, were there eating cheese.

“Cheese, cheese, cheese was on everybody’s lip and in everybody’s mouth. All you heard was cheese. All you saw was cheese. All you smelt was cheese. It was cheese, cheese, cheese. Streams of cheese were going up in the avenue in everybody’s fists. Balls of cheese were in a hundred pockets. Every handkerchief smelt of cheese. The whole atmosphere for half a mile around was infected with cheese.

“I sniffed it in every breeze. I rushed with the crowd to get a bit, and even with a look I would have been content—but alas unhappy me! I got no cheese. I smashed my hat in vain—I pushed over negroes, and jammed up bonnets—I pushed and writhed and struggled in the crowd, and maddened at last with desperation, I mounted the very shoulders of the mass for cheese. But it was gone! All gone! Naught but a few straggling, suspicious crumbs were left when I reached the table on which it had been spread. Col. Benton had a lump, on which he was expatiating [speaking at length]. Oh how my mouth watered for that lump of cheese. To the day of my death I shall remember, I got no cheese.”

Indeed, at the end of two hours the cheese was gone, except for that which had been ground into the carpet or smeared on the drapes which doubled as hand towels.

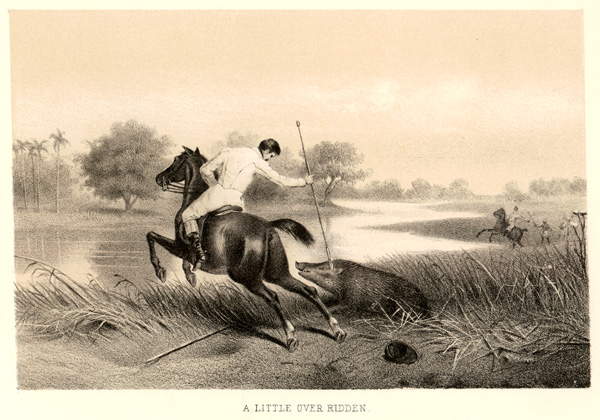

![]()

Illustration (uncredited) from Perley’s Reminiscences of Sixty Years in the National Metropolis (1886) by Benjamin Perley Moore

On February 25, 1837, the New York Spectator printed this account headlined “Correspondence of Commercial Advertiser” and dated February 22nd:

“We have had various excitements of late—abolition excitement, Texas excitement, exploring expedition excitement… and this day, the anniversary of the birth of the only Washington, the great and good father of his country, brought with it cheese excitement!

“It had been officially given out in the Globe [the ‘house’ newspaper of the Jackson administration] that the President’s mansion would be thrown open to the people on this day, and that they would be entertained with a cheese, sent from your own state, my dear editors, four feet in diameter! two feet thick!! and weighing fourteen hundred pounds!!! a cheese which, according to the official organ, beats quite hollow the great cheese that was made an offering to Mr. Jefferson, as the most appropriate present the farming class could tender to the President!

“The play-bill of the manager of the Theatre Royal, Little Pedlington [a fictitious theater in a satire by John Poole], did not present more attractions, or a more powerful cast, than did the invitation in the Globe. Who could resist it? No one. The whole city was on the move; and as the morning was mild and sunny, Pennsylvania Avenue was quite gay and animated with the various groups rapidly wending their way to the White House, or as it sounds more pleasantly to the royal ears, the Palace.

“The Senate caught the spirit of the hour, and adjourned about one o’clock, on motion of Mr. Benton. The House attempted to hold on… nothing was done but making motion after motion for adjournment, and calling the ayes and noes, and discussions whether they should go or stay.

“The spectacle at the President’s home was a strange one. The rooms were not only crowded to overflowing, but the hall, the doorway, and every vacant place around were filled. People had poured in from Baltimore in the railroad cars, from the country in all sorts of vehicles, and the steamboats and stages from Alexandria were so crowded as to render passage by any of them extremely hazardous. The company reminded one of Noah’s ark—all sorts of animals, clean and unclean. There was quite a superabundance of the latter for the rag-a-muffins of the city had got into the gardens—thence clomb to the terrace—and thence entered by the windows into the East Room. The marshal of the city and his deputies did their best to keep the canaille [lowest class of people, from the French and Italian for “pack of dogs”] from entering by the front door, but ‘the boys’ were too clever for them and got in by the windows!

“I forgot the Cheese. It was served up in the salle-à-manger [the translation means “dining room” but neither the State or Private Dining Rooms were used for the occasion; the writer is using the phrase to refer to the Vestibule] and the whole atmosphere of every room, and throughout the city, was filled with the odor. We have met it at every turn—the halls of the Capitol have been perfumed with it, from the members who partook of it having carried away great masses in their coat-pockets. The scene in the dining-room soon became as disagreeable as possible, and I gladly left it, after a brief observation, and mingled with the beauteous and brilliant throng in the East Room.”

Another account was written by Nathaniel Parker Willis, one of America’s most popular writers at that time, and appeared in his Loiterings of Travel in 1840.

“I joined the crowd on the twenty-second of February to pay my respects to the President and to see the cheese. Whatever veneration existed in the minds of the people toward the former, their curiosity in reference to the latter predominated, unquestionably. The circular pavé, extending from the gate to the White House, was thronged with citizens of all classes, those coming away having each a small brown paper parcel and a very strong smell; those advancing manifesting, by shakings of the head and frequent exclamations, that there may be too much of a good thing, and particularly of a cheese.

“The beautiful portico was thronged with boys and coach-drivers, and the odor strengthened with every step. We forced our way over the threshold, and encountered an atmosphere, to which the mephitic gas floating over Avernus [a crater in Italy which emits poisonous vapors] must be faint and innocuous. On the side of the hall hung a rough likeness of the General, emblazoned with eagle and stars, forming a background to the huge tub in which the cheese had been packed; and in the centre of the vestibule stood the ‘fragrant gift,’ surrounded with a dense crowd, who without crackers or even ‘malt to their cheese’ had, in two hours, eaten and purveyed away fourteen hundred pounds! The small segment reserved for the President’s use counted for nothing in the abstractions.

“Glad to compromise for a breath of cheeseless air, we desisted from the struggle to obtain a sight of the table and mingled with the crowd in the east room. Here were diplomats in their gold coats and officers in uniform, ladies of secretaries and other ladies, soldiers on volunteer duty and Indians in war-dress and paint. Bonnets, feathers, uniforms and all, it was rather a gay assemblage. I remembered the descriptions in travellers’ books, and looked out for millers and blacksmiths in their working gear, and for rudeness and vulgarity in all. The offer of a mammoth cheese to the public was likely to attract to the presidential mansion more of the lower class than would throng to a common levee.

“Great-coats there were and not a few of them, for the day was raw, and unless they were hung on the palings outside, they must remain on the owner’s shoulders; but with a single exception (a fellow with his coat torn down his back, possibly in getting at the cheese), I saw no man in a dress that was not respectable and clean of its kind, and abundantly fit for a tradesman out of his shop. Those who were much pressed by the crowd put their hats on; but there was a general air of decorum which would surprise any one who had pinned his faith on travellers. An intelligent Englishman, very much inclined to take a disgust to mobocracy, expressed to me great surprise at the decency and proper behavior of the people. The same experiment in England, he thought, would result in as pretty a riot as a paragraph-monger would desire to see.

“… by four o’clock the guests were gone, and the ‘banquet-hall’ was deserted. Not to leave a wrong impression of the cheese, I dined afterwards at a table to which the President had sent a piece of it, and found it of excellent quality. It is like many other things, more agreeable in small quantities.”

An editorial in the Poughkeepsie Eagle of March 1, 1837, took a less rosy view of the day:

“We perceive that General Jackson on the 22nd ult. ‘cut his big cheese’ in honor of the day. As vermin have ever a great fondness for that article, as was to have been expected, the government rats rushed in great numbers to secure a share of the spoils. In a short time the whole cheese, weighing 1,400 pounds, was carried off. The proceedings were so purely Republican that hundreds of loafers crowded into the East room and made free with everything they found there.”

After its consumption, the cheese of Thomas Meacham left a lasting legacy at the White House. In March of 1837, when newly elected President Martin Van Buren moved in, his new home still smelled of cheese. In 1838, he told a dinner guest, Eliza Bancroft Davis, wife of Senator John Davis of Massachusetts, that he had to air the carpets, dispose of the curtains, and whitewash and repaint the walls to be rid of the aroma.

In 1839, President Van Buren sold the last of Meacham’s cheeses (doubtless kept somewhere other than the White House) with the proceeds going to charity. The National Intelligencer noted:

“A cheese weighing 700 pounds is now at the store of Mr. William Orme, near the corner of Eleventh Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, where it will remain entire for one day, and will afterwards be sold in quantities to suit purchasers. It is from the dairy of Colonel Meachem of Orange [sic] County, New York, by whom it was presented two years ago to the President [Van Buren] of the United States, and has been preserved with great care. Having been made expressly for the President and by a gentleman whose cheeses are in high repute, it may be supposed to be of the very best quality.”

![]()

In Sandy Creek, a marker stands at the site of Thomas Meacham’s farm, “Home of the Big Cheese.”

Which brings me to the second mention of cheese, by Marcia, who recently made a batch of Sausage Cheese Balls. As someone who loves sausage and cheese almost as much as accuracy in research and writing, I asked for the recipe. Marcia’s generous reply:

“Super easy… 1 lb of Jimmy Dean HOT sausage, 1 lb of shredded sharp cheddar cheese, 2 cups of Bisquick. Mix those ingredients together WELL… make into little balls and bake at 325 degrees for 25 minutes. YUM.”

And there you have it: the story of Andrew Jackson’s cheese party and something special to bake, should you ever be invited to one like it. Thank you, Shannon and Marcia. And hail to thee, Sandy Creek!

![]()